No figure – including that glorious tall-tale-spinner Buffalo Bill Cody – is more riddled with confusion, controversy and misinformation than that hero of the Alamo, David (Davy) Crockett (1876-1836). Despite a strong predilection for all facets our Western Myth, I must confess that Crockett and other early frontiersmen have never really been of particular interest to me. I am too young to have been consumed by the great Crockett fad started by Walt Disney in 1955, when America’s youth actually wore coonskin caps and went about singing The Ballad of Davy Crockett. (“Born on a mountaintop in Tennessee/Greenest state in the land of the free/Raised in the woods so knew every tree/Kilt him a bear when we was only three/DAVY, DAVY Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier!” and so on for some 20 verses.) This fad was as pervasive and as powerful as the furor that surrounded Elvis Presley and the Beatles – if less pernicious than either – and those who were true believers seem never to have lost the faith. Believe it or not, I once worked for the head of a global public relations firm who was still so besotted by the Crockett craze of his boyhood that he still wore a coonskin cap. Now that is devotion.

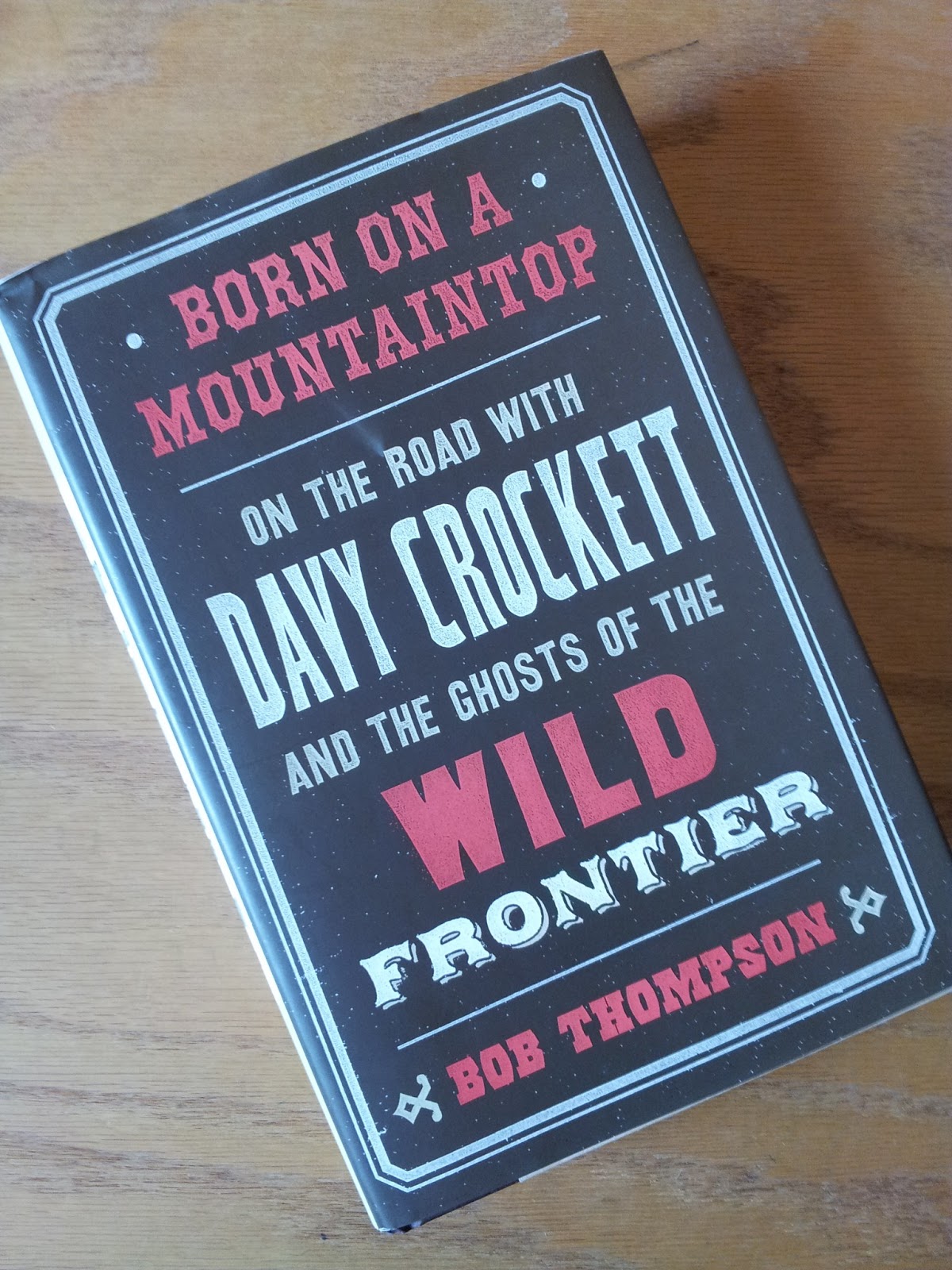

However, Davy Crockett has now come magically alive to me in Bob Thompson’s delightful Born on a Mountaintop: On The Road With Davy Crockett and the Ghosts of the Wild Frontier, and I finally see why the Crockett myth is so compelling.

For those looking for a straightforward biography, Thompson’s book will come as a disappointment. Instead, he goes after something much more interesting and personal. Much in the manner of Footsteps biographer Richard Holmes, Thompson writes a book literally pursuing his subject. He traces the historical Davy by following him through Tennessee, westward, and then to Washington, where he served two terms in Congress. We go with Davy on a book tour through Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York, and then retrace those fateful steps to Texas and the Alamo.

Though chasing ghosts, Thompson is extremely aware of the difficulties inherent in this method. He writes: “The past is a foreign country,” as the novelist L.P. Hartley wrote, but I think that Hartley understated the problem. The past is a foreign country that’s impossible to visit. You can’t just skip across the border, hire yourself a translator, and ask old John Crockett where he was on the afternoon of October 7, 1780 — let alone get up close and persona with his celebrity son.

The historical Crockett he finds is a man of contradictions. Born dirt poor, he received little education. He fought the Creeks and took part in several important skirmishes in the Indian war. After several unsuccessful attempts are raising his standard of living, he married (after his first wife died) a woman of modest means, but still of relative means. He became a local politician and ended up going to Congress – first as a supporter of Andrew Jackson, and then as his bitter enemy.

The paradoxes are many. Here was an Indian fighter who went to Congress and bitterly fought Jackson on an illegal Indian land grab. He was really “the poor man’s friend,” but he hobnobbed (or tried to) with Eastern Brahmans. He concocted the most outrageous tall tales about himself, but took umbrage (mostly) when others did so. Losing his seat in Congress – thanks mostly to Jackson (a man who makes Stalin look like Mother Theresa) – he heads West again and becomes embroiled in the battle for Texas liberty.

How and why? Well, Davy’s time in Texas is just little more than the last three months of his life, but Thompson devotes more than a hundred pages to it. Like all men, Davy was complicated and self-contradictory. He really did believe the fight in Texas was “the good fight,” but he also saw it as a way to revive his flaccid political career, and maybe get some land out of the deal.

Thompson starts the book by explaining that his two young daughters became interested in Crockett after hearing Burl Ives sing the Ballad, and how he spent years becoming fascinated himself. He also spends a great many pages on the Crockett craze of the 1950s, and examines where fact and fiction overlap. (Not very often is the verdict.)

Thompson was a longtime features writer for The Washington Post, and his Born on a Mountaintop is an eccentric, elliptical, solipsistic and often discursive book. However, it is also a fascinating read and an interesting meditation on Americana, past and present. It comes highly recommended.